Red Card to Rio: Violent Conflict

With the World Cup firmly behind it and the 2016 Olympic Games fast approaching, Brazil’s second largest city is embroiled in a resurgent level of crime due to a complex socioeconomic environment.

With the World Cup firmly behind it and the 2016 Olympic Games fast approaching, Brazil’s second largest city is embroiled in a resurgent level of crime due to a complex socioeconomic environment.

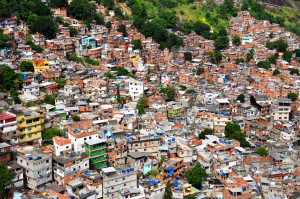

Rio de Janeiro is a sprawling mega-city with a metro population exceeding 12 million people and a density of 16,100 people per square mile—twice that of Los Angeles—that maintains a unique design. Nestled among a series of mountains along the Atlantic Ocean, the city’s most affluent districts are clustered close to the waterline and lower areas of the mountains. The city’s poorer inhabitants, however, live in the numerous shantytowns, commonly called favelas, which run up the mountains’ slopes.

Over 600 distinct favelas exist within Rio’s jurisdiction. Historically, each favela operated as an autonomous ‘micro-city’, usually under the explicit dominance of drug gangs while the city, state, and federal governments maintained a degree of separation between the lawless shantytowns and the more affluent areas under their control. The decentralisation has led each favela’s inhabitants to develop their own identity, causing them to associate themselves more with their micro-city than with Rio as a whole.

That sense of exclusion-based community has grown as a result of the racial and economic divide within Rio. According to the country’s 2010 census, Rio’s favelas are 60 percent black, while only 7 percent of the city’s wealthier districts’ population is black. Amplifying the geographic racial divide, while only 49% of Brazilians reported themselves as white, the same group earned more than twice as much as Black Brazilians.

The favelas’ secluded nature acted as a barrier for modernising forces. As a result, the favelas have been deprived of infrastructure, education, municipal services and plumping for decades, as gang presence blocked or scared away outside groups offering those services.

Prior to 2008, the Brazilian government turned a blind eye to favelas. Gangs proliferated in favelas, and drug traffickers were eager to fill the power vacuum the government left behind. They took on the role of vigilantes, punishing crime swiftly and severely. Husbands caught abusing their wives, for example, would typically be beaten and killed. This form of justice, combined with the jobs and capital the gangs pumped into each favela’s economy, created a romanticised picture of the traffickers in the eyes of the populace, increasing their tolerance for the gangs’ control and violence.

Beginning in 2008, however, with the imminent arrival of the World Cup and Olympics, the Brazilian governed began a campaign to pacify and regain control over the favelas. Focusing primarily on favelas near tourist areas, police and military forces began clearing them of drug dealers and started maintaining their gains by establishing a permanent presence in those areas. The favelas close to the wealthy areas fell quickly and were efficiently brought under government control. Although the favelas closer to the jungle and outskirts of the city largely remain in gang hands, the permanent police divisions, named Pacifying Police Units (UPP), succeeded by 2014 in pushing the city’s homicide rate down 37% from 2008, and are developing plans to regain control over more of Rio.

Despite their success, police forces have been criticised for coercion and excessive violence. However, most favela residents are not concerned with the police’s tactics as much as the question of what will happen following 2016. When the Olympics are over and the international spotlight is moved away from Rio, many residents fear the police will repeat history and leave them in the hands of the gangs again, effectively ending the government’s promises of introducing healthcare, education, and infrastructure to the favelas. These tensions were likely a motivating factor behind the mass protests throughout Rio in early 2014, when favela residents perceived the federal government was allocating more money to preparing for the World Cup than meeting their promises of improving life in the favelas.

The federal government has worked to pacify nerves by passing legislation in 2013, requiring the UPP to remain in the favelas until 2028.

However, UPP presence has not eliminated violence entirely. Over the past year, gangs have murdered dozens of police officers both on and off duty, resulting in increased police presence in the areas. Since the start of 2015, 13 people have been wounded in increasingly common shootouts between police and drug traffickers. The rising violence has led many favela citizens to abandon their hopes fostered since 2008 of welcoming the tourist trade into their communities.

Rio’s government and police have spent the past six years preparing for the World Cup and the Olympics by regaining control over the city’s numerous favelas, however with violence rising and confidence in the police’s commitment to security shaken, the lasting impact of the UPP mission remains to be seen.