Mexico’s Troubled Elections: A Fourth Wave of Democracy?

As the National Electoral Institute of Mexico (INE) released the preliminary results of the 2015 elections, international analysts quickly hailed the midterms as a symbol for budding democracies. In a press release following the elections, the Organization of American States recognized the “triumph of Mexico’s democratic system.” Similarly, only hours after ballots closed, political analysts immediately praised the surprising victory of multiple independent candidates – chief among them, El Bronco, an incumbent who built a campaign on disdain for mainstream politicians.

Yet the story untold remains that; despite INE’s efforts, Mexico just witnessed a violent electoral cycle, reminiscent more of the pre-democratic years than an international model for democracy.

In the months preceding the June 7 elections, 20 candidates for public office were murdered during campaign related activities. According to SinEmbargo.mx, a digital news journal, the tally reveals this year’s electoral cycle as the most violent in history, exceeding even the 2009 cycle, at the height of Mexico’s drug wars. In fact, if the data includes all degrees of physical aggression, the journal reports 43 campaign-related aggravations between February 18 and May 18, a number reminiscent of the political assassinations of Ayotzinapa in September.

Since that fateful day, Mexicans have gathered across the nation in widespread protests against government corruption, non-representation, and collaboration with violent groups. Most recently, the insurgent civil movement took two drastic actions preceding the national elections.

In the politically embattled south, the National Coordinator of Educational Workers (CNTE) – a national teacher’s union known for frequent protests – boycotted the elections through violent measures, resulting in the militarization of four Mexican states to ensure the installation of polls by election day.

Simultaneously, the CNTE and other anti-political groups called for citizens across the nation to nullify their vote and peacefully boycott the federal elections. Unlike the former strategy, this second movement gained national traction, spurring widespread counter-activism by citizens, journalists, and the INE to ensure the boycott’s failure.

The results demonstrate the failure of these movements with 47% participation rates and only 4.76% nullification rates (3% over and 0.2% under the 2012 rates, respectively). Nonetheless, the protests successfully captured international attention, with many analysts anticipating the elections to demonstrate “voter frustration” nationwide.

Furthermore, despite the acclaimed normalcy, electoral irregularities were commonplace on election day. Nationally, a scandal broke involving several Mexican celebrities who reportedly tweeted in favor of the Mexican Green Party (PVEM) for financial gain.

Locally, in the border municipality of Ciudad Juarez, radio commentators warned of rumors of purposefully delayed openings and erasable voting chalk, for which they recommended bringing pens from home. While the rumors are not nationally recognized, they demonstrate a widespread disillusionment with the political apparatus, including the INE, a neutral electoral agency.

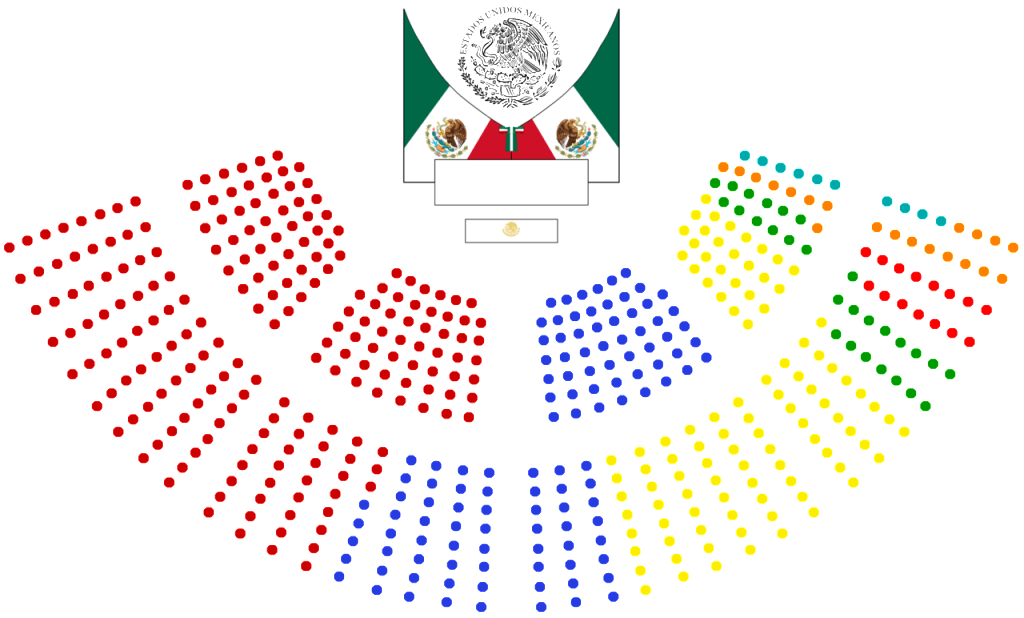

Nonetheless, voter frustration translated into an expected majority victory for the ruling party coupled with an unexpectedly large number of seats in Congress awarded to smaller contenders. Members from the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), won a plurality of votes (29%) and roughly 200 of the 500 seats of the lower chamber. The historic opposition party, National Action (PAN), retained the second highest number of seats with over 100 representatives elected. The remaining 200 seats are distributed among eight parties, four of which entered the national registry for the first time this electoral cycle (see graphic).

Despite violence and national adversity, citizens have sought out solutions by rewarding alternative parties and candidates while opposing the mainstream. Many observers have labeled these elections as an unprecedented and shocking event, yet they are not a first. The present state of politics suggests, rather, a fourth wave of democratization for Mexico – a nation speckled with struggles for political representation throughout its history.

Each moment has seen an opening, conflict, and a settling into a new, more representative reality. If Benito Juarez began Mexico’s modernity with his anti-clerical and indigenous reforms, Porfirio Diaz was his antithesis. If the Mexican Revolution saw a social transformation into federalism and cross-sector incorporation, the PRI’s 70-year dictatorship was its ugly cousin.

The 1968 student massacre in Mexico City reinvigorated civil society, and by 1989, the PAN had treaded unprecedented waters through their elected-victories in the north. For the first time in centuries, change became possible without a military leader as its symbol, and, save for the dirty wars and political assassinations, change had come to stay – through the Presidency of Vicente Fox.

Everything changed then – people now believe fair elections are possible, despite the country's overwhelming violence, corruption, and long-standing political repression.

The recent years saw a different Mexico.

Through Ayotzinapa, and the PRI’s return to the presidency, Mexicans have witnessed, tired, and risen again to face undemocratic trends. The election’s violence reveals an insurgent society; the electoral irregularities expose unrepentant political elite; and the results – society’s call for change.

Once more, Mexicans seek representation, only this time, absent of corruption, secrets, and lies.