Georgetown Hosts Latin American Drug Trafficking Conference

On February 10, Georgetown University’s Latin American Student Association, Mexican Student Association, and Por Colombia held a conference to highlight drug trafficking in Latin America. The event used Mexico and Colombia as case studies to explore the history, challenges, and possible solutions to the ongoing War on Drugs. Featured guests included Georgetown Professors John M. Tutino and Oliver Horn, Wilson Center Latin American Fellow Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, Francisco Thoumi of the International Narcotics Board, President of the Inter-American Dialogue Michael Shifter, and other prominent figures in Latin American politics and policymaking.

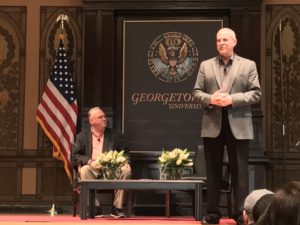

The symposium included three sections followed by a keynote address delivered by Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Agents Steve Murphy and Javier Peña, the inspiration for the Netflix hit “Narcos.” Section one established the historical contexts that led to the emergence of drug cartels in Mexico and Colombia. The second part, titled Repercussions, deconstructed the social, economic, and political challenges presented at local, regional, state, and national levels by various illegal organizations. Finally, the third portion evaluated potential policy solutions for addressing the consequences of the drug trade and the necessity to balance enforcement and rehabilitation.

A crucial producer and pathway for illicit drugs, Latin America serves as the geographic locus for discussions surrounding drug trafficking. Throughout the region, drugs paved the way for an upsurge in violence, environmental damage, the erosion of the community, the rise of guerrilla and insurgent groups, and political instability and corruption. Now, the governments of Latin America stand at an important crossroads where their histories must be addressed, their successes and failures determined, and the future influenced by policies that redefine the scope and approach to the War on Drugs.

For over 50 years, the War on Drugs, led largely by the United States with the support of some Latin governments, imposed a variety of unintended, negative consequences on the communities of Latin America, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Beyond the impact of the drugs themselves, the prioritization of punitive measures and enforcement often centralized power in the hands of organized crime and disproportionately affected individuals for minor offenses. Additionally, the intensity of prohibition created a power vacuum that facilitated the spread of vast drug networks throughout much of Central and South America.

The conference’s panelists emphasized the seeming failures and repercussions that perpetuate the War on Drugs, challenging the traditional enforcement paradigm. The panelists urged the audience to reconsider the use of enforcement, not as an illegitimate and completely ineffective policy, but as the entirety of a governmental strategy.

Adam Isacson, Senior Associate at the Washington Office on Latin America, attested to this by noting that “whatever success has been achieved is not measured in kilograms.”

Simply put, strategies emphasizing the reduction of supply-distribution channels alone cannot address and resolve the issue. It is vital, the panelists argued, that policymakers consider the demand-supply element of the drug trade, and therefore, begin to redefine the war on drugs by approaching the crisis as a public health concern rather than merely a criminal offense.

However, this paradigm shift heightens the debate surrounding the drug trade. In a recently published opinion piece in the New York Times, former President of Colombia César Gaviria addressed this polarization between enforcement-driven approaches and rehabilitation-based strategies. In the article, Gaviria urged Filipino President Duterte, known for his active purges of Filipino drug lords, to avoid making his mistakes. The letter cited the assassinations, widespread fear and violence, the endemic spread to other countries, and the overwhelming cost as projected outcomes of strict enforcement.

Panelists such as Georgetown Law Professor Álvaro Santos defended the complete decriminalization and legalization of drugs, modeled after the policies of the Netherlands and Portugal. For Santos, it is vital to acknowledge the failures of absolute prohibition and the benefits of recharacterizing addiction as a public health threat, prioritizing rehabilitation and reintegration into society rather than inflicting costly and ineffective punitive measures.

Downplaying the practicality of legalization, Dr. Francisco Thoumi, member of the International Narcotics Control Board, recognized the necessity of a dual response that balances both enforcement and rehabilitation. Thoumi argued that a society legalizes a drug through changes in culture, identity, and thought over time. Citing the case of marijuana in the United States to defend his assertion, Thoumi stated that, on the whole, it is impractical to believe that all drugs will and should be universally legalized.

DEA Agents Steve Murphy and Javier Peña touched on this divide through personal accounts from their experiences and roles in the fall of infamous drug lord Pablo Escobar. Steve Murphy stated simply, “we cannot arrest ourselves out of the problem. We cannot eliminate the enforcement arm, but what does that mean we advocate?”

Ultimately, the agents acknowledged the necessity of a balanced response as well as the importance of families and upbringing in counteracting the drug epidemic.

“Families should take more responsibility for their children,” Murphy concluded.

By addressing the socioeconomic and political motivations that facilitated the rise of drug cartels, the conference provided a sense of reflective engagement, encouraging innovation, peace, and a balance between enforcement and rehabilitation. Ultimately, the conference embodied Georgetown University’s foundational principles by offering a forward-thinking dialogue focused on constructive change in the global arena.