Development and Ethiopia’s Oromia Region - A Conflict Unresolved

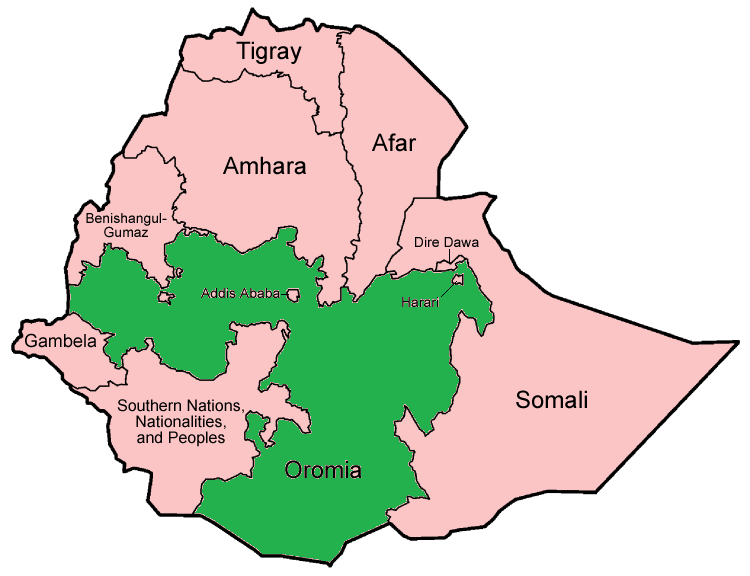

It wasn’t more than seven months ago that President Obama stood at the National Palace in Addis Ababa and called the Ethiopian government, which claimed to have earned 100% of the vote in its recent elections, “democratically elected”. Not more than four months later, an estimated 140 people of Ethiopia’s Oromia State are dead at the hands of that government. Conflict sparked early in November after Oromia’s regional government had approved the Master Plan – the national government’s large-scale development project. Students from various schools and universities organized nonviolent demonstrations in protest of the decision, seen by many as an invasive land grabbing scheme aimed at threatening the Oromo people and culture.

Although Ethiopia’s Constitution guarantees the right to peaceful demonstration, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn warned that the government would take “merciless legitimate action against any force bent on destabilizing the area.” The protests were met with just that as Agazi, Ethiopia’s Federal Police, violently attacked, arrested, and shot demonstrators. For weeks the violence continued; houses were burned and reports claiming the use of sprayed chemicals to poison students have surfaced. The Agazi’s violent response to peaceful protests has incited some Oromo groups to retaliate against the government as well as Amharas in the region, members of the second largest ethnic group in the country following the Oromo people.

These violent protests were triggered despite Ethiopia’s authoritarian regime. In 2014 the government introduced its new regional development plan that has come to be known as the Master Plan. The Master Plan, approved by Oromia’s regional government, sought to expand the capital, Addis Ababa, into the towns of the surrounding Oromia region.

The implementation of the plan was likely to cause the eviction of millions of Oromo farmers from their land and livelihood. For the Oromo people, the plan presents itself as a risk to autonomy and a mechanism for greater marginalization.

The Ethiopian government claims to have put an end to the Master Plan, but the history of violence in the Oromia region hints that the situation is far from a peaceful ending. Violations of guaranteed citizen rights are not something new to the region. The Oromo people, who have historically been marginalized by the greater state, have continued to suffer under the current government; Oromo children, farmers, and intellectuals have suffered abuse, kidnapping, imprisonment, and even death. Ethiopia’s ethnic federalism political system has further exacerbated tension with the government. The Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO) governs the ethnic-based Oromia regional state; theoretically the OPDO serves as a representative of the Oromo people, but the two decades of violence and crime committed in the region have brought their true motives into question.

The current ruling party has been in power for the last 25 years, and has a clear emphasis on an economic focused form of development. As the capital’s population steadily increases, a genuine abandonment of plans to expand into surrounding Oromia regions seems unlikely. A change to the master plan, one that the Oromo people would approve of, seems just as improbable. Even amidst the claimed cancellation of the plan, some protests and government crackdowns are suspected to still be occurring. It seems as though this period of relative calm is only temporary and further conflict in the region may be inevitable.