Border Upon Border

The most primal human instinct is the will to survive. In the modern era, as some countries face climbing violence rates and stagnating economies, people from those countries have begun searching for better lives, within and without the lines drawn on the map.

The most primal human instinct is the will to survive. In the modern era, as some countries face climbing violence rates and stagnating economies, people from those countries have begun searching for better lives, within and without the lines drawn on the map.

In the Western Hemisphere, the issue of illegal immigration is not monopolized by the United States and Mexico. Over the past three years, individuals from Central American countries, especially Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, are taking up an increasingly large portion of the migrants who are illegally crossing borders into Mexico and the United States.

Since the start of the decade, people have been fleeing Honduras and Guatemala’s rising murder rates. The problem is especially endemic in Honduras, which houses San Pedro Sula, the deadliest city in the world where 169 out of every 100,000 people are murdered.

Despite a declining murder rate, El Salvador has been overrun with cartel activity. Gangs have become so powerful that El Salvadorian president Salvador Sánchez Cerén recently admitted to soliciting MS-13, one of the largest gangs in the country, for support on his campaign.

Recent economic growth among Central American countries, attributable to a free trade deal with the United States, has failed to stem the flow of migrants. In countries such as Honduras, where the police and government have failed to provide security, people, most under the age of twenty, are looking north for safer opportunities as private citizens have been forced to defend themselves against the violence.

While domestic factors have played the primary role in pushing individuals to leave their home countries, Mexico and the United States have indirectly contributed to the rising levels of Central American migrants crossing their borders.

In 2006, then Mexican president Felipe Calderón went to war against the cartels, using the Mexican Army to push out a number of the weaker gangs in the country. Those cartels moved south into Central America, where they have developed greater influence than they ever enjoyed in Mexico. The rise in cartel presence in Central America has been linked to the rise in violence and murder rates in the region. To escape the cartels many Central Americans began migrating to the United States on paths that took them through Mexico.

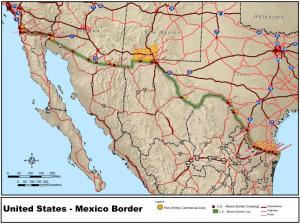

As the number of illegal migrants rose, Mexican authorities cracked down on immigration. Authorities have setup checkpoints along common cross-country paths and have removed migrants from La Bestia, the long freight-trains migrants ride north to the U.S. border.

Mexican efforts have resulted in the deportation of 30,000 Central Americans, two-thirds of whom were unaccompanied minors.

The high rate of deportation has lead to a noticeable decrease in the number of migrants crossing into the United States, a phenomenon that critics have been quick to label as indicative of Mexico positioning itself as the U.S.’s ‘bouncer.’ Serigo Aguayo, a professor at El Colegio de México, defined the dynamic as, “We are now the servants of the U.S. in this role.” Regardless, Mexico’s crackdown on illegal immigration has become so effective that may illegal immigrants have decided to seek asylum in Mexico rather than risk the dangerous trip further north.

Despite the Mexican crackdown, record numbers of Central American migrants—the majority unaccompanied minors—are still crossing into the United States.

In November, the presidents of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador met with Vice President Joe Biden at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) to discuss means of improving human rights and economic development in the three Central American nations and remove the motivation for potential migrants to leave their home country.

At present, the WOLA talks have not transitioned into policy. Consequently, violence and weak domestic economies are still incentivizing Central Americans to migrate north in search of more favorable conditions.

The incentive for child migrants, however, runs deeper. Current U.S. unaccompanied minor deportation laws have given potential migrants in Central America the perception that children who cross into the United States alone will be able to remain there permanently.

Under U.S. and international treaty law, child migrants from non-abutted countries must be tried prior to deportation. With over 50,000 unaccompanied from Central America apprehend crossing the border during the 2014 fiscal year, U.S. immigration processing facilities have been pushed beyond capacity, pressing the average length of a deportation case to over 500 days.

While awaiting trial, minors are sent, at government expense, to stay with relatives already living in the United States. Some experts estimate at least 80 percent of apprehended minors have family in the U.S., scattering the detained minors across the country. With fear of the courts and potential deportation haunting many of those relatives, many of the children miss their court date and remain in the United States.

This phenomenon has led many Central Americans to falsely believe children have the opportunity to remain in the U.S. indefinitely once they cross the border.

The issue of illegal immigration links Central America, Mexico and the United States together. As the number of migrants rises, it remains to be seen what steps Mexico and the United States will take to enact a long-term solution.