America, the West, and the Violent Politics of Exclusion

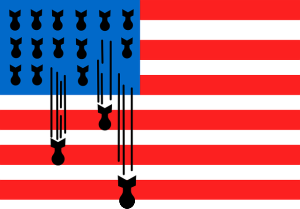

Yet the failure of America’s response to terrorism isn’t just its alienation of Islam, but also its obsession with ideological violence in general. In fairness, most far-right groups don’t use violence to achieve their political ends. And although reactionaries still constitute the majority of domestic terrorism, ideological violence itself is a sliver of overall violence in this country. To strengthen national security, U.S. officials and defense agencies should put their resources towards the common methods and circumstances through which violence manifests, not its sometimes rhetorical vehicles. Much homegrown terrorism could be prevented with better gun regulation, economic policy, and mental health programs.

But this uptick in white terror is symptomatic of a larger and more hard-to-buck trend: the resurgence of exclusionary middle class values across America and the West.

With hundreds of thousands of immigrant lives at stake, radical right-wing movements in Europe threaten to revert the continent to a darker era. Dutch politician Geert Wilders, a huge force behind reactionism across the region, describes the mass migration as an “Islamic invasion” that jeopardizes “the security, culture, and identity of Europe.” Wilders’ party currently ranks atop Dutch opinion polls. Far-right parties pushing the same xenophobic populism now lead public opinion or even governments in France, Sweden, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and elsewhere. The latter four countries outright rejected Europe’s refugee integration plan. And in a particularly unbelievable display of historical ignorance, the Czech government recently required all incoming Syrians be identified with serial numbers tattooed on their forearms.

Back in the United States, the popularity of Donald Trump may best mark the surge of intolerant politics. Among other frightening proposals, the GOP frontrunner calls for a solution to America’s “Muslim problem,” as well as the immediate removal of 11 million illegal immigrants. If the general election were tomorrow, CNN predicts Trump would win about 43% of the vote.

While we are well-equipped to reduce the direct violence on the margins, it’s the masses I fear most. It’s the masses who can demand such radically violent political outcomes—like those offered by the likes of Trump, Wilders, and other leaders—through deceptively nonviolent, mainstream political means.

From 9/11 to the current Syrian exodus, great crises are often the bases from which mass movements are born. These movements are important for national survival—and can be beautiful reminders of the very ideas that our Western democracies were founded on (e.g. freedom, brotherhood, and equality). But the same moments of solidarity can just as easily stir a related yet warring set of beliefs, just as present as Western ascendance, namely, cultural supremacy and persecution. Consequently, we end up indicting not just persons, but entire peoples.

After the January 11 Charlie Hebdo massacre, French intellectual Emmanuel Todd criticized the ensuing public rallies as the imposition of white middle class dominance, fraught with Islamophobia and even anti-Semitism. Todd was immediately excoriated by his fellow countrymen, including the Socialist Prime Minister, who described Todd as “self-flagellating” and unpatriotic.

This type of uncritical, with-us-or-against us unity is not unlike what emerged in America on September 12, 2001. In essence: “Critics be damned! Only with hindsight—and perhaps a bloody reprisal of Iraqi proportions—will we let you climb out of the woodworks and lecture us about the consequences of our fear-mongering.”

This recurring cycle of fear is dangerous and unsustainable. In the long-run, public education and policies that promote and protect rigorous inclusivity are important for moderating excessive responses to national uncertainty. More immediately, during and after crises themselves, bold leaders need to defend those on the margins as equally integral to our national projects. German Chancellor Angela Merkel already set an example of this leadership when she proposed Germany accept 500,000 new refugees. And since then, outbursts of compassion have emerged all across Germany to rival and even drown out the new roars of racism. Hospitals, schools, churches, families, and even soccer leagues are all frantically preparing to welcome the incoming migrants.

In the United States, President Obama did well last week to increase America’s refugee goal by 30,000, now 100,000 in total. Yet that 100,000—one-fifth of the German objective—sounds more like lip service when considering that America enjoys 26 times Germany’s landmass. Far from mobilizing ourselves to confront the crisis, Americans tend to dismiss it as an exclusively European problem.

If not now, when will we take a true stand against the violent politics of exclusion?