Compass World: And the Rest is History

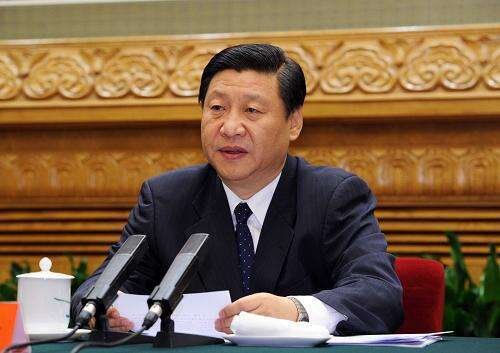

Chinese President Xi delivers a hardline speech in commemoration of the Korean War. “The Chinese people don’t go looking for trouble, but nor do they fear it.” (Translation provided by the Washington Post.) (Baidu Commons)

by Claire Cheng (SFS '24)

A 20-episode docu-series on the Korean War is currently being aired daily across China’s national TV broadcaster (CCTV). This docu-series is part of China’s weeklong national celebration of the 70th anniversary of its entry into the Korean War, or, as the CCP calls it, the “War to Resist American Aggression and Aid Korea.”

The commemoration was kicked off by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to the national military museum, followed by a public letter to Korean War veterans, and capped by a stirring and hawkish speech signaling Chinese resolve to stand up against its competitors—namely, the United States. Xi’s voice rang through the Great Hall of the People in Beijing: “Confronted with any hardships or dangers, the calves of their legs will not shake, and their backs will not bend.”

All of this is strategic. The intensity of rhetoric used in anniversaries of this war ebb and flow to the currents of U.S.-China relations. In 1970, following the resumption of U.S.-China diplomatic talks under President Nixon, China, seeking better relations, did not hold a 20th-anniversary celebration, instead seeking to downplay any historical antagonism. However, in 2000, after an American bombing of a Chinese embassy in Belgrade during the Kosovo War, and during a period of continued deterioration in U.S.-China relations, Beijing held a commemorative ceremony with six thousand officials in attendance. Chinese leader Jiang Zemin visited veterans, and Beijing hosted a museum exhibit memorializing the war.

Similarly, the highly public and inflammatory nature of this year’s celebration is indicative of the current high-strung relations between the two great powers.

Why the Communists Party

The Korean War, fought from 1950 to 1953, is often invoked to arouse anti-U.S. sentiment in China. On October 19, 1950, Mao made the fateful decision to send Chinese troops to side with North Korea against U.S. troops backing South Korea. The war holds symbolic meaning for the Chinese: it represents the triumph of Eastern communism over Western capitalism and imperialism. It is also a story of the victory of the underdog.

Well… not a complete victory. The war technically ended in a draw, with joint Soviet, Chinese, and North Korean forces pushing U.S.-led UN Command forces back to the 38th parallel, where it all started. To this day, no formal peace treaty has been signed to officially end the war.

Mao’s risky decision 70 years ago framed one of the most contentious issues underlying U.S.-China relations today: Taiwan. China’s “victory” in the Korean War was crucial to helping the new communist country (fresh out of a civil war) establish a sort of national identity and prove its strength to a skeptical international community. But it may also have squandered one of China’s best opportunities to capture Taiwan in a rare moment of diverted U.S. attention and weak Taiwanese national unity.

The Korean War arrived barely a year after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. China was weak—militarily, economically, and politically. Mao had just emerged from a divisive and bloody civil war against Chang Kai-Shek’s nationalist forces, which retreated to Taiwan in May of 1950. The U.S. promised not to take sides in the civil war, at least not explicitly.

That all changed on June 25, 1950. Kim Il Sung’s North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel, which demarcated the boundary between Soviet-backed North Korea and U.S.-backed South Korea. At the onset of the war, China had no intention of intervening beyond providing moral support to Kim Il Sung. The U.S., afraid of seeping Soviet influences in the region, immediately led UN Command forces to reinforce South Korea and push into North Korea. Fearing that Soviet influences could also reach the newly-established Taiwan, President Truman deployed the U.S. 7th fleet to secure the Taiwan Strait.

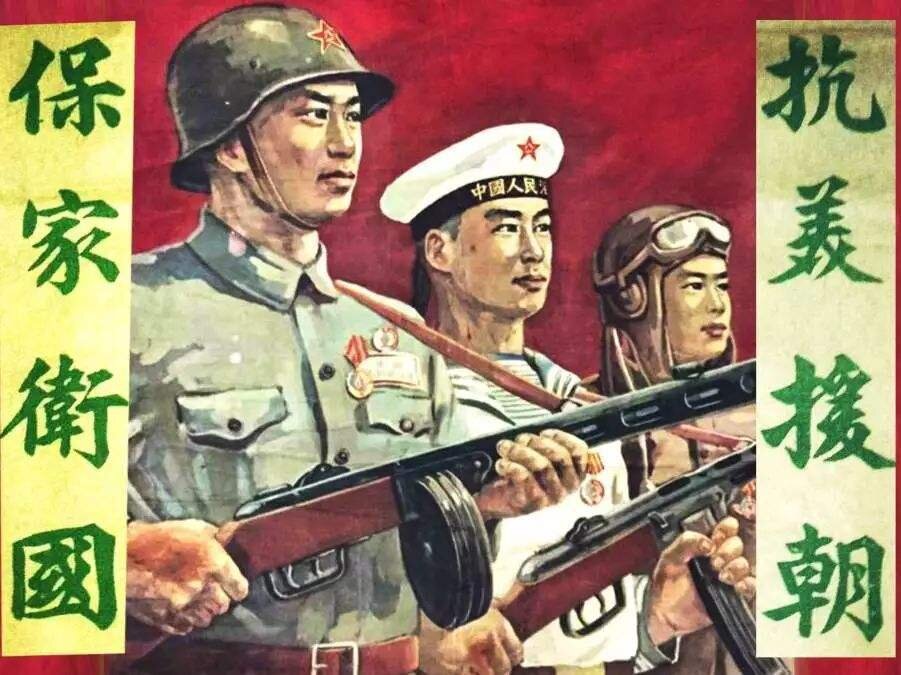

Chinese propaganda helped generate public support for the war. The right reads “War to Resist American Aggression and Aid Korea.” The left reads “protect our homes and defend our country.” (Translation provided by author.) (Baidu Commons)

This move angered the Chinese. Truman had blocked Mao’s ability to attack Chiang and stymied his ultimate mission to reunify Taiwan. According to Shen Zhihua, a history professor at East China Normal University, “[t]he intrusion of the U.S. 7th Fleet deprived the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) legitimacy to liberate Taiwan, as well as blocked their way to land on the island … such a move ignited Mao’s anti-American anger.”

Mao had regarded the U.S. as an imperialist power seeking to encroach on Chinese sovereignty ever since the end of World War II. Mao insisted China could not sit by and do nothing against the ‘foreign imperialists’ sitting at their doorstep.

There was another consideration at play. The border between North Korea and China was marked by the Yalu River. Most of China’s manufacturing industry was then located in the northeast, near the Yalu River border. When the U.S. invaded North Korea, China felt threatened: the destruction of its manufacturing industry would be lethal to its industrialization and development.

The decision to intervene was not an easy one. Mao knew he would be matching up against one of the strongest militaries in the world that could dominate in the air and the seas. But Mao regarded U.S. involvement in the war as an existential threat along with its presence in the Taiwan Strait. Mao proclaimed China needed to enter the war to “protect our homes and defend our country.” (In Mandarin Chinese, "保家卫国.")

Here lies the critical juncture. Mao threw his support behind Kim, putting his mission to capture Taiwan on hold. Mao viewed the liberalization of Taiwan as a task that awaited him following the Korean War. Little did he know that his window of opportunity was short-lived. The U.S. later solidified its support for Taiwan, and Taiwan’s leadership consolidated—and the rest is history.

Playing the Hero, Making a Villain

While the war is regarded as a draw on paper, Chinese leadership considers it a momentous victory because the cards were stacked overwhelmingly against them. Underrated, under-equipped, and under-armed, China fought its way to a draw by matching guns with human shields and human bullets. The place where Chinese troops crossed the Yalu River was dubbed by troops as “The Gates to Hell.”

American POWs captured by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) in the Korean War. (Wikimedia Commons)

Years later, there’s still debate over whether Mao’s decision to intervene was right. Most of the Chinese troops employed in the war were volunteers in the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (CPVA). The official Chinese government reports the Korean War claimed a total of 180,000 Chinese lives. However, the number could be as high as 900,000. Li Shenzhi, a pro-democracy academic, reported on the conflict for the Xinhua News Agency: “Mao dragged China into it because he wanted to be a hero.”

China was at a crossroads in 1950: either it could lend support to North Korea and stand up against an encroaching, imperialist U.S., or it could use that war as a diversion to cross the strait and capture Taiwan. China chose the former—and that has made all the difference.

Seventy years later, with the benefit of hindsight, the Korean War is cast in a new light. It is a war that came with great benefits at a great cost—a war that laid the foundation for China’s strength and legitimacy, but it was also a war that left an unresolved conflict, which has become China’s greatest thorn.

The fracturing of U.S.-China relations under the Trump administration has prompted many scholars and journalists to more closely scrutinize the Korean War—one of the only instances of direct military confrontation between the two contemporary superpowers. The irony is 1950 China was cooperating with North Korea to counter the U.S.; fast forward to the Obama administration, and roles reversed: the U.S. began to increase cooperation with China over North Korea. As relations sour under Trump, those cooperation efforts dissipated, all while the U.S. ramped up pressure on the Taiwan question. Would anything change under Biden? If not, expect celebrations to stay big.